10/10 The Creator is a searing tapestry of emotion, an uncompromising labyrinth of peak action scenes, a scorching hate letter to American imperialism and exploration of the human cost of war measured in screams.

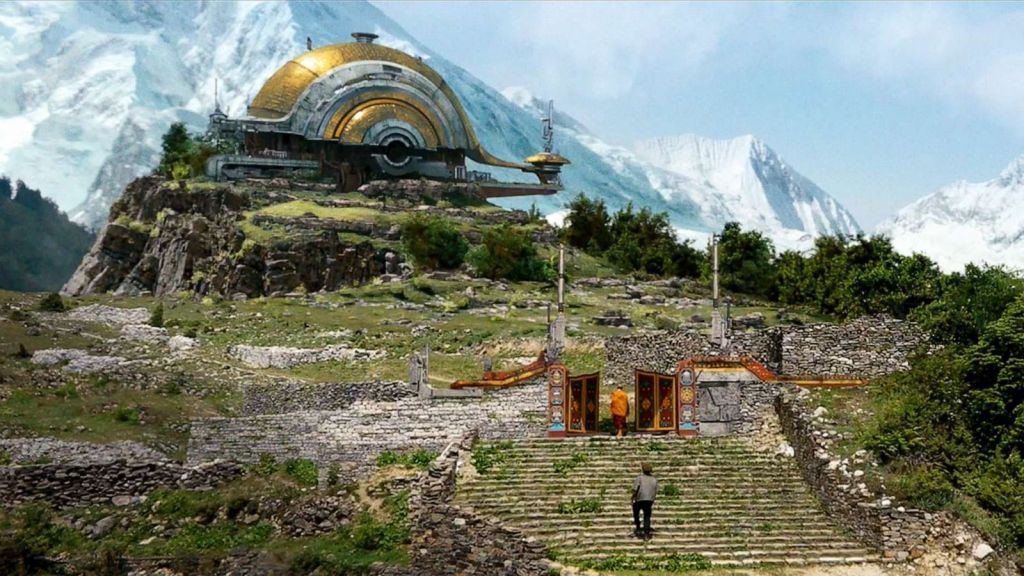

The Republic of New Asia, 2065- In an alternate history Earth where fully functioning artificial intelligence is developed shortly after World War II and 10 years after a rogue program nuked Los Angeles, the U.S. has banned all artificial life forms and wages a brutal war against New Asia, a confederacy of what appears to be all the countries underneath the elbow formed by India and China from Nepal all the way to Vietnam on the coast, which became a haven for the machines. Sgt. Joshua Taylor (John David Washington), on a long-term undercover mission to find Nirmata – Hindi, “the creator” – a mysterious engineer behind recent AI advancements who the machines worship as a creator god, is caught unaware when American forces attack backed up by the USS NOMAD (North American Orbital Mobile Aerospace Defense). The space station, an all-in-one spy satellite and nuclear weapons platform that can seemingly cover the entire war by itself, is a massive blade that hangs ominously in the sky, the Sword of Damocles dangled carelessly over an entire continent.

Another five years later, Nirmata has built a new weapon capable of destroying NOMAD. Taylor, now a dejected veteran cleaning the rubble of Los Angeles, is lured back to New Asia with evidence that his wife, Maya (Gemma Chan), who was also his main subject of surveillance, survived the attack. He discovers the weapon, the first ever AI child called Alpha-O (Madeline Yuna Voyles), capable of controlling technology remotely through what appears to be prayer, whom the machines worship as a messiah. On the run from both the American military and the New Asian police, he shepherds the child across the continent in search of Nirmata.

The Creator is stunning. It’s awesome! It’s sweeping in scope with breathtaking photography, a 133-minute adrenaline rush of sci-fi action and horror underlaid with religious questions on human worthiness, surprisingly frequent punchlines and a consuming lost love story. A real strength of the film, and a way it stays at 100 the entire time, is that it’s essentially a miniseries – it’s segmented into five acts with different titlecards, each of which end on the type of action scene that put the climaxes of many lesser films to shame. It’s the blockbuster your mother warned you about! It’s everything!

This is writer/director/producer Gareth Edwards’ masterpiece, the culmination of his work going all the way back to his 2010 feature debut Monsters, the little-seen indie film that bagged him the jobs for Godzilla and Rogue One: A Star Wars Story. The saying goes that all directors have one movie they keep making over and over, and that’s very much what his career looks like – Monsters is the story of a photojournalist and his daughter forced to walk through a quarantine zone full of gigantic alien monsters. His Godzilla movie was similar, but couched in an established intellectual property and frequently criticized for its lack of action, as I suspect Rogue One would have been if it weren’t essentially taken away from him.

The Creator will never be criticized for a lack of action. The Creator brings the goods. The movie opens cold with an astonishing, massive-scale sci-fi action scene and idles at 100 mph for the entire runtime. It reminds me of Tenet from 2020 for a lot of different reasons, but that’s the biggest – no matter what else, it’s unimpeachable because the action is brutal, satisfying and almost constant.

It’s another feral performance from John David Washington, who brought a snarl and rage to Tenet that elevates a character who was written to be a blank slate. Viewers learn almost nothing about Tenet’s protagonist except his stated motives, and we unravel the mystery of the film through his perspective. In The Creator, the snarl is still there elevating a character who also holds the audience at arm’s length, but in different ways. Taylor spells out his backstory in depth, but his motives are dangerously opaque. It’s unclear whether or not he’s truly gone native on his undercover mission or where his loyalties lie after the timeskip, unclear to the audience because it’s unclear to Taylor himself. He’s barely holding it together. His frantic need to find Maya again, which already overlaps with his assignment to find Nirmata, grounds the film, allowing it to operate at a global level, the level of this individual war and the personal level all at the same time.

Washington can take a lot of credit for the film’s sense of humor as well, breaking down at the perfect moment midway through several lines, but Edwards and cowriter Chris Weitz have blessed him with perfect lines for that type of transformation – for instance, the gem “Let’s play a game. It’s called, ‘Help your friend Joshua not get killed by the friggin’ police,’” where he’s code-switching all the way from child-friendly to a desperate fugitive mid-sentence, is another way the film lets itself be several things at the same time. Editors Hank Corwin, Joe Walker and Scott Morris lend everyone perfect comedic timing, which Alpha-O benefits from greatly.

Before anything else, The Creator is gorgeous. To save money, and this is a big reason why Edwards was able to get it done, the backdrop of this sweeping sci-fi world was created by photographing real-world settings in Southeast Asia, keeping the animated elements sparse and only painting them on after the edit was already locked.

That seems like a common-sense thing, but if this were a Disney production, it’d be created primarily through animation and look like a pile of crap. This style of production has been the doom of blockbusters over the past few years and remains an underlying factor in a lot of the labor unrest we’re seeing. It’s one thing for someone like me to complain about Marvel movies, but it’s entirely different when decision-makers are watching a film that looks much better than their $300 million productions for a fraction of the cost.

The product is extremely tangible and fantastic at the same time, but also extremely colorful. The greens of the Asian countryside are stressed during day scenes, but Edwards and photography directors Greig Fraser and Oren Soffer go out of their way to use heavy reds and blues in night scenes. Little towns exist mostly as they were found, but are dominated by massive structures extending into the clouds like the proverbial beanstalk. The technology in this film reaches up into a future we aren’t prepared for, and these background elements seem to exist only to visualize that idea. All the physical elements of production are left over, smoke in the air, water droplets, grain in the night scenes. It all looks so real because most of it is.

What The Creator does so well, and what sets it apart from a movie with the same imagination but lesser execution, is it shows its technology in impoverished settings. That’s what makes it so real. Just as my smartphones and flatscreens don’t look like space age technology set up in this old project from the ‘60s, the machines don’t look like miracles from an alternate history while living in rural wooden shacks. This is also what makes the film so urgent to this moment in American and technological history, when news breaks seemingly every day of some dubious new advance in technology that is frequently referred to as “artificially intelligent” by salespeople. It looks like the same dystopia with different specifics that might make it more obvious – a satire, then, and it is a frequently funny film.

It certainly feels like a satire watching soldiers with exoskeletons straight out of “Mass Effect” and light rifles designed to punch through metal simulant bodies march on yak farmers backed up by NOMAD’s sensor array, this wall of blue light from a satellite that holds an entire subcontinent at gunpoint following behind them, and still be so paranoid of their own safety. That does start to make sense, though, as they frequently run up against NOMAD-imposed deadlines – the military tacks a missile strike onto the end of every mission, a pattern that is hopelessly faithful to the other attitudes it displays.

The Creator is transparently, almost to the point of sarcasm, about the Vietnam and Iraq wars and the American police state in general, both in obvious ways like mostly being shot in Thailand and the details like pointedly referring to the Los Angeles site as “ground zero.” Everyone holds their war losses like a rosary, never blaming the war itself but always directing a fury toward the machines that can’t help but betray that whatever screed is mantric, self-brainwashing.

As heavy-handed as the film is about war’s propaganda, it’s just as scathing and thorough about its horrors. The Creator misses no opportunity to show the most visceral consequences – Taylor uses two artificially intelligent prosthetic limbs after being caught near the Los Angeles blast. This makes his wounds present even when he isn’t lingering on them, but also serves his character beautifully. As his loyalties remain unclear, his naked body is either missing an arm and a leg or almost half machine, but he appears fully human when he’s dressed.

Violence in The Creator is always punitive, with the American military’s technological superiority matched only by its cruelty applying it. Civilians and scientists are constantly shot in surprise attacks, unarmed, in the back, on the floor, you name a scummy way to kill someone, these soldiers do it. Highlights include one character falsely surrendering, holding her hands up after calling in a strike on the people who are trying to take her alive, and the mass execution of AI monks, dressed in Tibetan robes and lined up on their knees.

The Creator is a symphony of people and machines screaming for their lives. A common weapon is a sticky, timed-bomb launcher, which latches onto a target and then counts down from long enough that the victim and comrades get to frantically scramble to get the thing off. We see machines being crushed in giant compactors while they’re still writhing desperately to get out. Entire towns become a chorus of terrified whaling as residents can see NOMAD lounging across the sky toward them. Late in the film, we see monstrous futuristic tanks that look about four times the size of an Abrams bulldozing trees and firing on fleeing civilians.

Underneath all the other things that it is, The Creator is a simple psychological drama of a man letting go of his long-dead wife and coming to terms with the child she left behind, but the machines’ religious fervor takes that story and builds it out into this cosmic question. Taylor sees the heart of machine society, a fabricated religion observed by fabricated life forms. Are his gods also made-up? If belief in a higher power is the truest indicator of consciousness as the film seems to suggest, then when we create conscious machines, are we also creating their gods?

It’s easy to see the innovations Edwards brought to the Star Wars cannon carried over here in The Creator. In Rogue One, set just before the original Star Wars, the Death Star is shown destroying individual cities instead of an entire planet at a time – making it a much more useful weapon, a much more direct metaphor for nuclear weaponry and also much more impactful visually. You can’t shoot a planet being destroyed completely from the surface of that planet, but you can show a city being destroyed, so Rogue One puts viewers in proximity to a Death Star blast for the first time. Many of its best moments are simple shots of the station hovering menacingly in the sky in exactly the way NOMAD does in The Creator, apparently down to the precise level of interference from cloud cover. Several other design elements unique to Rogue One within the Star Wars universe appear to have been carried over to The Creator as well.

It’s no coincidence Los Angeles is the city Edwards chooses to turn into a crater. The Creator contains several jabs at Hollywood and seems to take issue with Rogue One in particular – it was the film that first introduced Disney’s unholy facial reanimation technology, forcing Peter Cushing, who had been dead for 24 years, to reprise his role from the original Star Wars for a legacy character who was certainly not the original screenplay. In The Creator, recently killed soldiers’ brains are scanned and plugged into synthetic bodies to extract information from beyond the grave, an application Taylor seems to see as just as necromantic and abhorrent.

This is certainly the movie Edwards been trying to make his entire career, emptying out several movies’ worth of ideas for action scenes, sci-fi conceits, philosophical concepts and shots into one densely packed and emotionally, intellectually and visually fulfilling ride. This is the type of movie that’s so good I get a kick out of the mere idea of it playing on a screen somewhere, joy at the thought of someone discovering it for the first time.

Leopold Knopp is a UNT graduate. If you liked this post, you can donate to Reel Entropy here. Like Reel Entropy on Facebook and reach out to me at reelentropy@gmail.com.

Pingback: ‘Godzilla Minus One,’ plus international acclaim | Reel Entropy