A member of the legendary class of ’99, I saw The Matrix twice in theaters last year for 25th anniversary screenings. This was after a 2021 re-release ahead of The Matrix Resurrections, the series’ corporate-mandated retrofit, which was actually my first opportunity to see it in a theater.

Seeing The Matrix at the giant IMAX on Webb Chapel was very much like seeing it for the first time. The soundscape, a weak point in home viewing, is rich and layered in a theater’s surround sound, bringing out details I’d never heard before almost immediately, but what I really notice is the lighting. Famously, inside the Matrix, everything has a sickly green tint, but it’s also just slightly blown out. In photography, “exposure” refers to the amount of light that a piece of film is exposed to – “overexposed” means too much light hit the sensor, “underexposed” means too little, and “blown out” specifically means so much light hit the film that details in the brightest parts of the image aren’t recoverable. Scenes set in the Matrix are deliberately and very slightly blown out, the whites just barely stretching into those characteristic burnmarks that stand out if you know what you’re looking for. It’s obviously an artistic choice, but it registers in your brain as a mistake, this constant reminder that something about the world onscreen is phony.

Possibly the most cinematic movie ever made in addition to its cultural staying power, this is one of those that should be on standby rotation for classics screenings. Most multiplexes have had regular classics days more than a decade now. It gives them some quality control for lower-end months and an opportunity to market to older viewers while keeping the magic alive, but during the COVID-19 crisis, this programming became a lifeline as theaters opened months before studios were willing to risk new content. This has stabilized into a market-proven canon of American classics set on a rough, five-year rotation – theaters like those fifth- and tenth-year anniversary numbers. Jaws is 50 now, that’s working its way around this week.

I’ve seen The Matrix on the big screen a fifth time in a theaters just now. Well, something resembling a theater, I guess-

Grandscape

In the deep reaches of Far North Dallas hugging the still mostly undeveloped south side of Sam Rayburn Tollway between Lewisville and Frisco, there’s a… place, I hesitate to call it a neighborhood, called Grandscape. Its website describes it as an “open-air lifestyle complex,” a description which captures both the mechanics of the place and the desperate waking nightmare of walking through it, as though your conscious self knows to pretend everything is fine while your lizard brain screams to wriggle out the back of your neck to safety.

The perfect setting, then, for a screening of The Matrix.

Inside Colony city limits, Grandscape is an enclave within an enclave. The more-than 400 acre plot opened in 2015 as a “unique mixed-use development” intended to serve as the entertainment hub for the newer office parks and “intentional neighborhoods” in the surrounding area. Far North Dallas and Collin County were the second-to-last areas of the DFW Metroplex to fill in – it will, of course, continue to stretch further outward until the trumpets sound and we are all called to account for our sins, but there are still stretches of undeveloped land between existing cities. Soon, urbanization will come for that 15 mile tract of Insterstate between Fort Worth and Denton where the city suddenly cuts off north of Grapevine Lake, but it’ll be similarly checkered around the existing, master-planned real estate developments already springing up in the area.

These are neighborhoods built for people who, 40 years ago, decided to take their money and get out of Downtown Dallas and are now demanding that the conveniences of dense urban centers come to them. Because this is all in the service of new-money Texans who vocally resent public services as well as imports who can both afford newly built mcmansions and want to fit into those neighborhoods, the areas that service them are all high-end shopping malls. Every square inch of land that is sold here is for the most expensive possible use. New apartment complexes are all “luxury,” and the old projects built in more reasonable times are re-billed as “luxury” as soon as ownership changes hands. Every bar and restaurant is boutique and garishly priced, and there’s nowhere else to go other than bars and restaurants. It’s not unusual to see blocks made up of a donut shop, three fast-casual joints that are either too expensive or too cheap and a nightclub interspersed with some old card shop out of its depth from before the area’s growth spurt or maybe a gas station, breakfast, lunch and dinner all in one parking lot and no other part of the human experience accounted for.

Grandscape aspires to be the largest of these entertainment blocks, loomed over by its “anchor,” a 100-acre Nebraska Furniture Mart, whose parent company Berkshire Hathaway owns the whole development, visible for miles around like a 100-foot tall brick of glass and advertising space, a nightmarish, day-of delivery perversion of the county courthouses that rightfully own the rural Texas skylines. The fact that a “lifestyle complex” is “anchored” by a massive warehouse full of what should be 30-year purchases is not a contradiction – this is a place for people who have been convinced that consumption is lifestyle, that they can be made interesting by the interesting things they own. The dwarfed Rooms To Go, Mattress Firm and Texas Leather Interiors stores across the tollway tell the story of a prime area for furniture retail that has been devoured in the womb by the old-money monstrosity dropped onto the highway from Omaha.

As you crawl your way east down Nebraska Furniture Mart Drive, you’ll eventually reach Grandscape proper, the much more recent cluster of restaurants, shopping centers and entertainment venues that are still smaller in total than the Nebraska Furniture Mart, complete with one modern apartment tower rising up over the south side for what must be spectacular views of the tollway, fields of remaining prairie ripe for further development, or the white expanse of the Nebraska Furniture Mart’s roof and parking lot. It’s the simulation of a neighborhood, complete with walking streets and private security to keep undesirables off their public furniture, there to help you enjoy the open container area of roughly a quarter square mile that connects with as many minigolf venues that also serve alcohol as it does bars.

We have all seen and experienced gentrification, the process of moneyed new developments pushing out the soul of a neighborhood, a mixed blessing at best that doesn’t always completely destroy what was already there as long as existing locals who care about maintaining their communities have a say. There were never any locals in Grandscape. This is not gentrification, it is an entirely new obelisk, built whole-cloth without a soul.

The Cosm

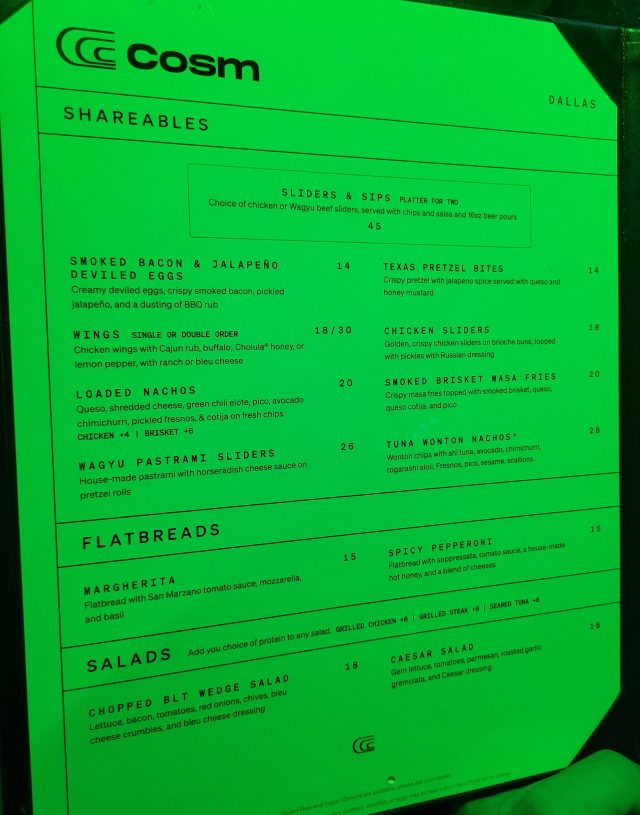

Deep within this lifestyle complex is a… well, it’s an over-designed three-story sports bar with way, way too much open floorspace to take reservations called Cosm. The west wall is a giant, convex omni screen on which they play sporting events full-frame. You’re supposed to pay to reserve your table to watch live sporting events here, with ticket prices comparable to nosebleed seats and then at least $100 more per person on food and drink for a full-length sporting event. The other half of the building is decorated by significantly smaller screens, presumably to stream different sporting events during busier seasons like a real bar.

In the summer, they’ve been drumming up business with movies – well, just one movie, The Matrix. They’ve been screening it twice a day, billed as The Matrix in Shared Reality, for three months. The film shown in the original 2.39:1 aspect ratio and the rest of the omni screen filled with a themed background to create a more immersive experience.

This is an interesting claim, because there’s actually nothing in the entire world more immersive than a normal movie theater. It’s a purpose-built windowless room, theoretically distraction-free, that hijacks your senses of vision and sound to create a shared dream for an audience – the concept of films as shared dreams is a whole branch of film studies from both a filmmaking and a cultural criticism perspective. Various attempts to increase immersion over the decades, such as vibrating seats or various waves of 3D, have proven to be ineffective fads.

It’s the correct choice of film. The Matrix concerns a dystopian future in which the remnants of the human race have been enslaved by artificially intelligent machines and held in pods so they can be used as energy. To pacify this enslaved population, they are surgically modified from birth to be plugged into a simulated reality called the Matrix, most living their entire lives not realizing they are in a simulation. The version of the Matrix we see appears to be an endless expanse of downtown Chicago permanently lodged in 1999 – one of the Matrix’ agents, imposing men-in-black types who police the Matrix from the inside, puts it on the nose late in the film: “The peak of your civilization. I say ‘your civilization’ because, as soon as we started thinking for you, it became our civilization.”

This is, of course, what this is all about – as The Matrix has moved further into history, its dystopia has become alarmingly more present. Forever wars became a fact of life, and storms of the century became annual occurrences. Decrepit world leaders focus on going through the motions of political theater long after the post-war order has shattered, simulating a more stable time in world history. And now, of course, large-scale computing, commonly billed as “AI,” simulates human artistry and relationships for the pleasure of people who, frighteningly, seem like they don’t know the difference.

I was curious. How would the Cosm fill its screen? Simply blowing the movie up would be an option, and it has been projected at 2.2:1 for 70mm prints, but it’ll only work to a certain point before the movie becomes unrecognizable. Maybe that’s what they should have gone for. I assumed the rest of the screen would be filled with some kind of cartoon, but The Matrix is an incredibly clever and detailed movie with a fanbase that loves those details, so there’s a lot of cool, creative things they could use the space for. On the other hand, if they wanted to simply expand the frame into a 1:1 while maintaining the original film within a correctly sized rectangle, AI image generators would be the ideal tools for the job.

Have we really moved this far beyond irony? Has someone used AI to make a new version of this film about the most famously scary AI dystopia in cinematic history? I had to find out.

Then I saw the pricetag and realized I didn’t have to find out.

Each ticket is – well, first of all, you can’t buy individual tickets. Cosm is set up as a sports bar with three levels facing the screen, and you can reserve individual tables for your party. The tables are all priced differently because you can’t see the entire screen from most of them – much less of a problem for a sporting event than a film. The least expensive per-person seats are a table for two, running $45 each, which I grabbed as a birthday present for a friend who’d wanted to see The Matrix in a theater for years. Food and drink prices are proportionate. I got a themed three-course meal, with Really Good Noodles, a steak and a cookie timed with their appearances onscreen, as well as my choice of Red Pill or Blue Pill themed cocktails. That was also $45, but it was the kind of perfectly rare steak you expect at that price point. My date paid $15 for a glass of Miller Lite.

This a post-Moviepass world, so we really need to put that price in context – I maintain subscriptions to both AMC and Cinemark, which combine to $30 for roughly 13 movie tickets per month, and I’ll spend $30-$60 a month on concessions based on mood. A double-feature at the Texas Theatre will run $20-25 for tickets, that’s a monthly treat.

I go to the movies once every three or four days, many of those in PLF houses, and one night for two at the Cosm costs a month and a half’s movie budget. This “experience” is priced to compete with about 20 nights at a regular IMAX.

The Matrix in shared reality

Now that we’re finally here, I’ve seen the expansion, and I’m comfortable it wasn’t AI – I threw on Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith when I got home and noticed that its Playstation 3-era backgrounds are roughly the same quality as the backgrounds Cosm added to The Matrix. For a digitally shot film, lower quality and with built-in tools to tie foreground and background together, this works, but for The Matrix, with its hand-built sets and expert rear-projection work all on crisp Kodak film, surrounding it with lower-quality images only takes away from the experience.

You notice this immediately – in the cold open scene, where Trinity escapes the agents, we see the molding, lived-in brick buildings as she runs across rooftops. The Cosm surrounds this scene with similar buildings, but no gradient, no graffiti, no visible decay, no character at all. It’s just not really an expansion of the film.

This is a constant refrain – The Matrix is one of the greatest artistic and technical achievements of all time. This is the draw for your $50 tickets, but also your limiting factor for an “experience” that alters the film. Every shot, cut and lighting choice of this movie is perfect. Any change you make to it is a mistake.

Even without changing it directly, the background mutes the film’s impact in several ways. Despite its scope, many of its most iconic moments are extremely claustrophobic, and adding in a background that expands the set takes away from that. Several later scenes cut back and forth between shots set in the always blown-out Matrix and shots aboard The Nebuchadnezzar, the dingy, shadowy hovercraft where we spend most of our time in the real world. The background expanding these shots will either stay the same or change over slowly, which noticeably blunts these cuts. Finally, the film features many sound cues of thunder and offscreen gunshots, which the background adds in lighting cues for. It’s cute, but adding a lighting cue where none existed is a big change for a film that, again, should not be changed in any way.

There’s a way to add to this experience, or at least make it significantly different, but that would require much more courage. Scenes with existing peripheries, like ones set in Neo’s office or the rooftop or subway fight scenes, currently decorated with a mostly static background, could have been recreated in much more detail shot-to-shot. Scenes that could be cropped differently and blown up to scale without truly altering them, like ones in the Construct program or the film’s many one-on-ones, would need to be expanded, perhaps even re-centered with new background details in various corners. The handful of shots when people or objects extend out of the frame need to be extended.

These are changes that would piss off a lot of paying customers, but frankly, if all you want is to watch The Matrix, you can stream it. That’s a better viewing experience even if it weren’t priced for people who live at Grandscape.

In order to justify its price point, the Cosm has to add something that makes a good movie better, and that’s impossible. The pitch here is “shared reality,” which is in practice just some matched screensavers on a screen that’s too big for most applications, but I don’t think that’s the actual pitch. Like Grandscape itself, The Matrix in Shared Reality is designed for people who have been convinced that consumption is a lifestyle, that interesting and overpriced things make you interesting and overpriced. That’s the assumption you have to make to buy a ticket, and from there, it’s just turtles all the way down. You bought this absurd ticket, you’ve come to this absurd place, maybe even had an absurd dinner or game of minigolf beforehand, so we’re pretty sure you’ll pay for this absurd drink, too. What are you gonna do, go to the gym? Crochet? Go to another store and buy different kinds of thing?

We are indeed watching The Matrix in shared reality, because in 2025, this is our shared reality, this simulation of a community inhabited by people who’ve been raised to think this is all there is to life and staffed by people who hate them. Because this is all that the people with money want to build, this is all that we have to look forward to, this soulless brick of concrete, Astroturf and artificial lakes flattening, paving over and expanding outward forever.