Writer/director Oz Perkins’ new masterpiece Longlegs is going to change horror forever. It’s an absolute knockout, eerie, haunting and disquieting while also just joyful enough to put several grins on your face.

Oregon, 1990s- FBI Special Agent Lee Harker (Maika Monroe), after demonstrating what appear to be clairvoyant powers, is assigned to the case of a horrifying serial killer who murders entire families at a time while appearing to have never even entered their homes. The only evidence of his existence are the encrypted, hand-written notes he leaves at the scenes, signed “Longlegs” (Nicolas Cage, who also produces).

Longlegs is a horror masterpiece for several reasons, but the best is the most surface-level – this movie is trying really, really hard to scare and entertain you. As disturbing as the subject matter is and as challenging as the film ends up being, you’re also in for a real show. Cinematographer Andrés Arochi’s every shot is breathtaking, usually in a distinctly scary way but sometimes it’s just generically well-shot, and what moments there are of levity are palpably joyful. You can feel when the film is having fun with you.

It’s a brutally slow film, made up of distant, static shots of its cavernous, nightmarish spaces – production designer Danny Vermette also gets full marks here. There are scant few jumps, but just about every shot is its own long scare. A lot of the film’s energy comes from its editing, credited to Greg Ng and Graham Fortin, which supplements many of these longer shots with subliminal flashes from Harker’s clairvoyance. This is where it starts to feel so high-effort. The film is a long, terrifying journey, but weirdly, you feel like you’re in good hands while watching it.

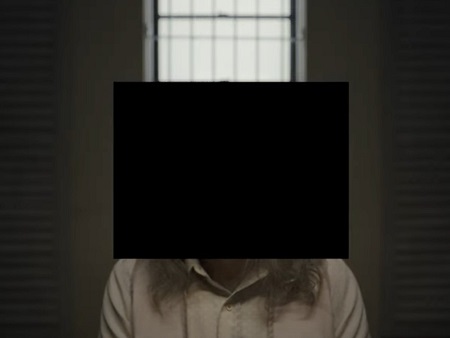

The highlight, and the best confluence of fun and fear, is another absolutely deranged performance from the national treasure that is Nicolas Cage. The man is magical. If he hadn’t been the best actor in the world for 40 years now, he’d be a legend for this performance alone. Longlegs is a film of extremes, extreme subject matter, extremely slow pacing, the use of Satan as the core villain, and it wouldn’t be the same film if the title character didn’t match the extremity.

Neon’s vivid guerilla marketing campaign quietly made Longlegs one of the most anticipated films of the year, and a lot of it was around building up Longlegs’ character design. It’s not quite as shocking as all that, but it’s a fantastic design that’s going to turn him into an iconic movie monster within the next few months. He’s a failed, ahead-of-his-time glam rock singer who had some botched plastic surgery a few years back, and that’s what he looks like, and that’s what he acts like. His room is full of posters of post-Invasion English rock bands, and he sings a lot of his lines. Maybe he made his deal with Satan in exchange for easier lyrics, or maybe he just took too much acid.

Longlegs is a Satanic film, and Satan is physically present from the first shot, but not quite a Satanic Panic film. It isn’t trying to convince your mom that Ozzy Osborne really believes all that crap. Instead, the Satanic Panic film about Longlegs turning into a monster already happened, and we’re left with a ton of Satanic Panic aesthetics in a movie about genuine evil. Similar to how Longlegs bends religion to his own ends, we see the film bending the sensationalism and assumptions of the Satanic Panic to its ends as well.

Monroe is also a star and the heartbeat of the film. Longlegs has been pitched as “Silence of the Lambs with more Satan.” That’s an oversimplification, and the key difference between the films is how Monroe plays Harker. Jodie Foster’s Clarice Starling is in over her head, frantic and perhaps too invested in her case, but she’s tough and game for every challenge she faces. Harker, by contrast, is scared. She’s unnerved by everything she sees, and her fear carries viewers through a journey that feels completely different.

Perkins had a soft breakout with his 2017 debut The Blackcoat’s Daughter – it premiered at TIFF but ended up releasing direct-to-video, so it’s both well-regarded and very obscure. Longlegs recycles the same plot to tell a much more complicated story about blind faith, be it in parents, the church, law enforcement or your own intuition, as well as Faustian bargains, Proustian memory and the subconscious urge to violence. The darkest tendencies of the human psyche are in every corner of the film.

The script is extremely rich and deceptively complex for a movie where not much happens, which gives it a great deal to rewatch value. The spine of it is in lines of dialogue that are, like the film’s crimes, repeated verbatim across decades, such that years of atrocities seems like one simultaneous event.

The repeated subject matter of a father killing his entire family and then himself maintains the film’s gravity, but the less specific fear of an adult man attacking physically weaker people who depend on him is always at the surface. Longlegs, who is set up as a vile father figure, is always shown approaching young girls or smaller women, so while there’s more going on in the mythology of the film, that’s always what you’re looking at.

Longlegs represents a shift in the “smart” horror genre, such a shift that it really represents a new subgenre of its own. Compared to something like The Witch, a masterpiece which is often seen as too slow and psychological to be effective for broad audiences, Longlegs maintains the heavy psychological elements, but it’s much more directly satisfying, made with an apparent love for several eras of horror. Longlegs himself looks like a bland Insidious/Conjuring monster, with the white facepaint and grin and reliance on atmosphere to become a real nightmare – obviously, Longlegs has much more atmosphere than those films. We also see a lot of the monster suddenly appearing in static shots and other playful background details that characterized Paranormal Activity and its offshoots. The harder elements, such as the use of Satan and thick splatters of gore in its murder scenes, seem lifted straight out of the ‘70s and ‘80s.

As popular and as high-quality as Longlegs is, it’s hard to figure who to recommend it to. It’s way too graphic for anyone who isn’t into hardcore horror, but because there’s so much to appreciate about it, it would be a great entry point for people who aren’t into hardcore horror, but want to be. It’s also a great introduction to the old-school art film movement of slow cinema. A much better movie for introducing both of these concepts, however, would be the 2018 masterpiece Mandy, also starring Nicolas Cage in one of his best performances – ironically, Panos Cosmatos approached Cage to play the cult leader in Mandy, but he preferred to play the lead, so Longlegs is sort of an expansion and reversal on that film.

With its not-so-surprising $22.4 million opening weekend draw against a budget of just $10 million, Longlegs is already a smash hit commercially. It’s now lined up to become the flagship of a distinct, much more violent subgenre for arthouse horror.

More importantly right now, it’s an unforgettable cinematic experience.

Leopold Knopp is a UNT graduate. If you liked this post, you can donate to Reel Entropy here. Like Reel Entropy on Facebook and reach out to me at reelentropy@gmail.com.