August may have been the best time to go to the movies in my life.

For the past months, movie news has been dominated by anticipation for and tracking of “Barbenheimer,” the release of both Barbie and Oppenheimer on July 21, and their results. Barbie stayed at no. 1 at the box office for four weeks, and Oppenheimer dropped to no. 5 only over Labor Day weekend, though this is partially due to the traditionally weak August release schedule.

Well, “dominated” is a strong term – this double-feature has shared the news cycles with the double strike, as both the Writers’ Guild of America and the Screen Actors’ Guild had begun striking by the time of release. The two news items collided dramatically when the actors walked off of Barbie and Oppenheimer’s star-studded press junkets a week before the twin premier, canceling what would have been an unconscionably fashionable red carpet premiere for Barbie.

‘Barbenheimer’

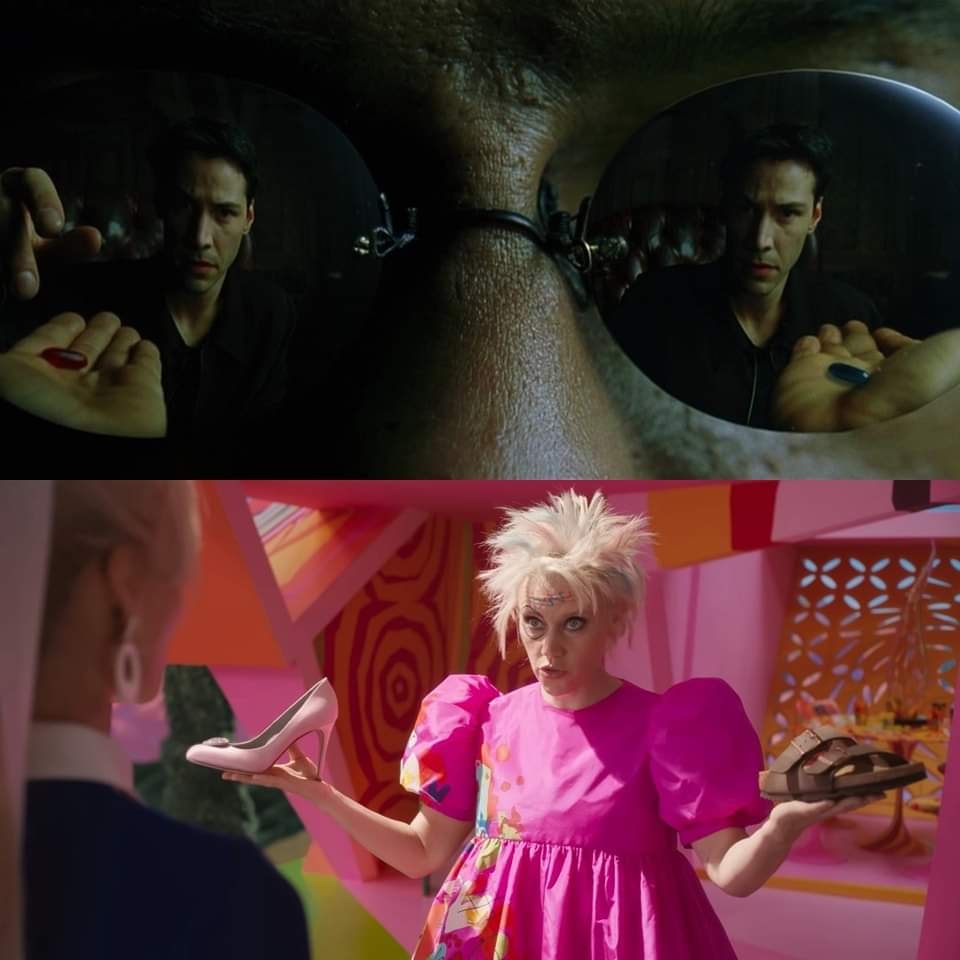

“Barbenheimer” became a meme because of mass audience response to the apparent clash between the films, but they have a remarkable thematic overlap. They are both stories about the mythological fall of man, each nicely folding in the Greek and Hebrew narratives about Prometheus stealing fire from the Olympians and the Garden of Eden, which descend into a dense, hopeless underbrush of toxic masculinity. Barbie is a slide deck laying these issues out in glossy pink bullet points, and Oppenheimer puts them all in motion and the context of real events.

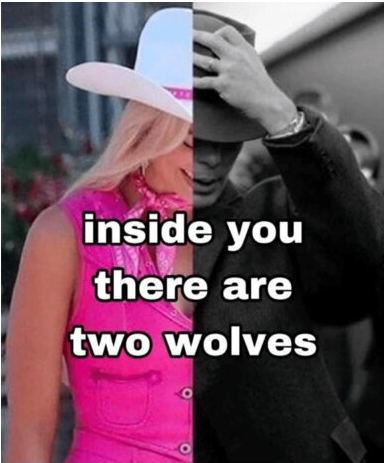

In Barbie, Barbie and Ken (Margot Robbie, who also produces, and Ryan Gosling) have been posited as an inverse version of Adam and Eve, beginning the movie in a pristine, feminized paradise, and each of them bring forbidden, dangerous knowledge to the masses. In the opening scene, Barbie is portrayed as the monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey, which teaches pre-human primates to use weapons, and girls are shown smashing the baby dolls that Barbie took the place of. The last act of the film is set in motion when Ken brings knowledge of the patriarchy and heteronormative relationships back to Barbieland.

In Oppenheimer, the title character is referred to directly as an “American Prometheus” – the film is adapted from a 2005 biography with this title – and the film goes out of its way to incorporate Garden of Eden imagery. In an early scene at Cambridge University, J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) loses his temper with his professor, Patrick Blackett (James D’Arcy), and injects cyanide into an apple left on his desk. The apple gets its own shot centered deliciously in the frame, its poison shade of green brilliant against the classroom’s browns, a single drop of what we know isn’t water caressing its curves. Oppenheimer wakes up the next morning in a scramble to prevent Blackett from eating the tainted fruit.

The scene directly mirrors Oppenheimer’s relationship with the atomic bomb, which is the focus of the rest of the film. He devises a cruel weapon with no defensive countermeasure and immediately realizes it should never be used, but it’s already out of his hands. Two hours of film time and 20 years later, after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the film cuts back to Blackett taking a lusty bite of what might be the same poison-green apple.

In Barbie, we see the eerie results of Ken inverting Barbieland’s gender dynamics, though the process is mostly offscreen, but over the entire three-hour runtime of Oppenheimer, we see the self-importance of Rear Adm. Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) slowly emerge as the main driver of conflict. Oppenheimer, consumed by guilt over his work, is confronted at every turn by characters who view that work as a stepping stone, from Strauss after the war to Col. Leslie Groves (Matt Damon) during it to President Harry Truman (Gary Oldman), who callously denies Oppenheimer’s guilt by assuming full credit for the bombings, to Edward Teller (Benny Safdie), who won’t stop working on his theoretically larger hydrogen bomb at Los Almos.

In their most frustrated moments, several characters shout about what is “important,” and the film ends on Strauss’ importance being insulted directly like this – this is immediately after he has a meltdown about his perception of Oppenheimer’s self-importance. Strauss’ bitter insults toward Oppenheimer, who is not in the room, are cross-cut with Oppenheimer retreating from similarly aggressive prosecution by special counsel Roger Robb (Jason Clarke) five years earlier.

There is perhaps no greater portrayal of toxic masculinity and the way American culture is currently shaped around it than Robb’s interrogation in this scene. Over the almost 70 years since this hearing, American politics has become a show of obstinance against any outside force, with a full industry centered around televised debates in which political candidates show off how firmly they will refuse to change their minds. A lot of this country’s decline can be traced back toward lawmakers’ relatively new view that the simple act of reacting to new information is a threat to their careers.

Robb seems to predict this dynamic in this scene, in which he dramatically screams accusations that amount to, “Your opinion changed! You said something slightly different almost 10 years ago!” His successful attempt to discredit Oppenheimer hinges not just on this accusation, but the accompanying invisible argument that this is a damning thing – the recent history of politicians harassing scientists for changing their answers in step with the science is also playing out in this moment.

As Strauss flinches at the insult, a moment that would be barely noticeable highlighted by a close-up, Oppenheimer’s pointedly human scale comes into focus. The atomic bomb was devised by humans, and in Oppenheimer, the subtle betrayals of the human face and layers of human communication are just as destructive and worthy of highlighting as the bomb. Oppenheimer’s downfall stems not from his outspoken pacifism, but the constant stream of needly little insults he directs at everyone around him.

The Apocalypse

After last August, Hollywood may never be the same.

SAG and the WGA share many of the same concerns about residual payment as streaming services take over show consumption and the use of deepfake and large language models, commonly referred to as “artificial intelligence,” to replicate actors’ images and manufacture screenplays, respectively. Streaming services have all but eliminated residual payments, a large portion of television actors’ and writers’ income, and studios have been threatening to use the models to reduce the amount of work available for actors and writers.

The immediate question may be, would a $200 million and up Hollywood-scale production really bet on the breathtakingly unreliable generative programs currently being referred to as “artificial intelligence,” and I mirror that skepticism – large language models are obviously not capable of replacing human writers, and the con artists blindly claiming they eventually will be are starting to come off it – but we’re already past that point. This year’s major Independence Day release, the $295 million Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, opens with a half-hour flashback starring a deepfaked Indy. Anthony Ingruber, an actor whose main claim to fame is an uncanny resemblance to a young Harrison Ford, apparently doesn’t resemble him enough, because they’ve plastered a computer-generated model of the real Ford’s face trained on footage from the first three Indiana Jones movies over Ingruber. He’s the star of the first half-hour of one of the most expensive movies ever made, and I don’t know what he looks like.

That movie bombed, by the way. Actually, there have been a lot of bombs this summer – Dial of Destiny, The Flash and Haunted Mansion are registering some of the biggest losses of all time, and even among movies in the black, Barbie is the only real runaway success. When you spend $265 million on The Little Mermaid, to keep picking on Disney, almost $570 million worldwide is probably good enough, but “good enough” isn’t what you paid $265 million to hear.

Backing up further, there have been a lot of bombs over the past several years. Studios have gravitated toward $200 million as a baseline budget for major productions, even though it obviously isn’t and movies keep failing specifically because they’re too expensive, and there isn’t a great answer why. I generally point to Disney’s astonishing string of billion-dollar successes with established properties over the ‘10s, which allowed them to drive up their own budgets and costs for the rest of the industry, but there’s significant confirmation bias talking there. What’s certain is that Disney’s production practices, which include wasting a ton of money on replicated VFX work to create low-quality movies that all look the same, is being imitated by competitors as they try to match films budget-for-budget.

The refusal to make movies at a price where they could possibly turn a profit coincides with the streaming wars, which have revealed that many of these same studios’ astonishing inability to make money with dedicated streaming platforms. Disney+, Paramount Plus and the Warner-owned streaming platform previously known as HBOmax are all reporting losses. Again, Disney is the most alarming name here – apparently Disney CEO Bob Chapek, instead of trying to make money immediately, was aiming for Disney+ to eventually be profitable in 2024 and happy to send blockbuster-sized investments like “Secret Invasion” straight onto the internet. He was shitcanned late last year.

It’s a crashing bubble. I’ve been writing about a crashing bubble on this site for 10 years now, and, interrupted by Moviepass and the COVID-19 crisis, this is basically what it was always going to look like. The result of funneling every dollar into major releases, all of which have their branded streaming platform ready and waiting, has been exactly what anyone should have expected – more access to fewer mainstream options, many of which are being made down the hall from each other under the same bosses, and with a new event movie in theaters every week, there isn’t enough money to go around. Everybody loses, nobody makes money.

Revelations

Barbenheimer made money.

When the films opened, they combined to lead the fourth largest domestic opening weekend of all time, making up 78% of a just-over $311.2 million total haul at the box office, more than double the previous weekend’s gross and by far the biggest weekend since the COVID-19 crisis closed theaters in March 2020 – the Dec. 17, 2021 date, headlined by the release of Spider-Man: No Way Home, is the only one that comes close. Their combined opening, and their weekend’s total numbers combined with everything else in release, are almost identical to those of Star Wars: The Force Awakens, which accounted 79% of a $313 million weekend on Dec. 18, 2015.

Barbie opened at just over $162 million, the no. 20 opening of all time and by far the biggest opening ever for a movie directed by a woman on her own – no. 2 and 3 on the list, Captain Marvel and Frozen II, were co-directed by a woman and a man, so you have to go down to no. 4, Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman opening with just over $103.2 million in 2017, for an apples-to-apples comparison.

Oppenheimer came in second with just over $82.4 million, the no. 111 opening of all time and by far the biggest ever for a movie opening in second place – no. 2 and 3 on that list, Sherlock Holmes and Alvin and the Chipmunks: The Squeakquel, both opened on Christmas Day 2009 underneath Avatar in its second weekend, so you have to go down to no. 4 on the list, Trolls opening with $46.6 million in 2016, for an apples-to-apples comparison.

Perhaps the most astonishing set of numbers is the way each film opened compared to initial tracking – they both roughly doubled what their expectations were as of the end of June. Box office forecasters, who use pre-sale data, internet traffic and a wealth of data on how particular audiences have behaved in the past to come up with extremely accurate predictions, were coming out of the woodwork to say they’d never seen anything like this.

The basic mechanic of counterprogramming, sliding a movie with apparently little audience overlap into the same release date as a major event movie to pull in viewers who wouldn’t see the larger release, is nothing new, and Barbenheimer should have been a textbook example. The real key with counterprogramming is different levels of family friendliness – Barbie is much, much more child-friendly than Oppenheimer, and we see that mechanic repeating with the Alvin and the Chipmunks and Trolls movies as well.

Barbenheimer instead caused a chain reaction, and enthusiastic audiences forced them into complimentary roles instead of contrasting ones. Plenty of ink has been spilled about how weirdly their marketing campaigns complemented each other and what an odd couple they seem like, and many actual couples pointed this out – one of the most delightful aspects of Barbenheimer was the fashion, with moviegoers dressing up for Barbie, the iconic fashion doll, and lending the same enthusiasm to Oppenheimer.

While Barbie was having people dress up to go to the theater again, Oppenheimer’s massive 70mm Kodak was packing people into the handful theaters that could show it in full glory. The full IMAX film format only ran in 30 theaters in the entire world, some of which were actually museums. I had my ticket for opening night more than a month in advance, and it took me more than a month to get a second ticket at that theater. I buy most of my tickets five minutes before I leave the apartment, this is completely unheard of.

It used to be like this. The entire phenomenon, the packed theaters, the screenings of real celluloid, the treatment of movies as major nights out to mark on the calendar, as events, functions as a mass callback to days of roadshows and movie palaces, the kind of organic enthusiasm for arthouse cinema I never expected to see again, certainly not in the foreseeable future. It would be in keeping with both films to call it prelapsarian.

Barbie and Oppenheimer had the most important demographic overlap of all – people who love movies. That’s really all it was. They both looked really, really good.

In a movie environment where major films have become a cynical guessing game of which sized-up action figure in front of a greenscreen will have the most supporters, Barbie and Oppenheimer both tick a lot of the same boxes – they’re both coming from name directors, they’re both major investments with significant advertising pushes behind them that aren’t cramming themselves into gigantic existing franchises and they both put a heavy focus on actually creating their realities, not drawing them in as a post-effect. Barbie drained the global supply of pink paint building all its sets, and the costumes speak for themselves. Oppenheimer writer/director/producer Christopher Nolan, known for rejecting computer effects, had been boasting for months in advance that his film about the atomic bomb doesn’t have any CGI in it, and it’s got the kind of period detail you expect from a high-end Oscarbate biopic. Both films were listed as among the most anticipated at the Hollywood Critics Association’s midseason awards, with Barbie taking top honors.

The pair’s incredible cultural and financial success turned Hollywood’s attention away from the months-long string of failures that preceded them, and the focus is now on which major releases will fall off the calendar because of the strikes, and after all that is sorted out and big-budget movie makers get back to work again, a bunch of advertising executives will look back on a year full of duds and try to figure out how to replicate Barbenheimer.

But Barbenheimer was not a product of advertising. The lesson major studios desperately need to take away from this, the secret ingredient that helped these movies succeed in a year when so many others have failed, is so simple they’re almost certain to miss it: they were both really, really good.

In the words of John Waters, “Make good movies, or die!”

Pingback: ‘Haunted Mansion’ sold at auction, leaving viewers with the leftovers | Reel Entropy

Pingback: Yet another TMNT movie, but this one’s pretty great | Reel Entropy