The Texas Theatre was built in 1931, and was nearly demolished three times in the ‘90s. It reopened under current management in the fall of 2010, and the Oak Cliff Film Festival has always been part of its identity under Aviation Cinemas’ management – they’ve been running the theater for almost 13 years, and this is officially the 12th Oak Cliff Film Festival, so the math is pretty easy.

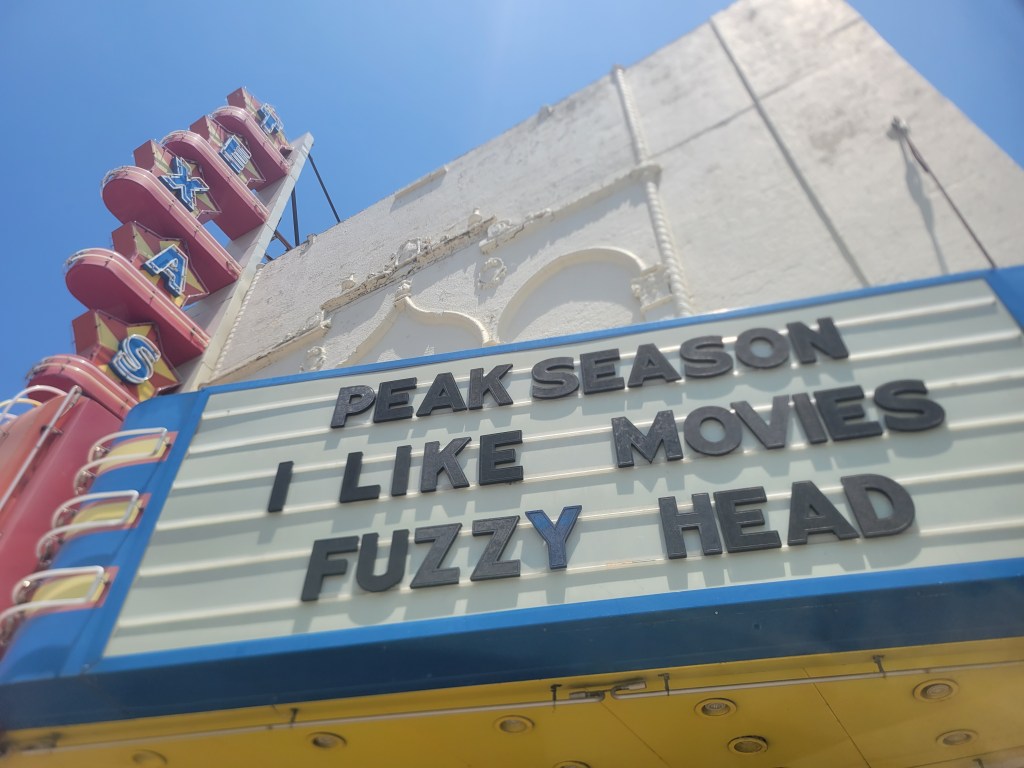

Given the historic nature of the place, it makes sense that restorations and 35mm prints are an enormous part of the theater’s programming, and an enormous part of these film festivals. On day 3 of the 2023 Oak Cliff Film Festival, my whole day is committed to movies I’ve either seen or could have seen before – Fuzzy Head, which I’ve seen early prints of after meeting the director at a prior Oak Cliff Film Festival, a 35mm print of Alex Cox’ 1987 film Walker starring Ed Harris with Cox on-hand to take questions, and a screening of 1925’s The Lost World with a live score performed by the Anvil Orchestra.

I arrive two and a half hours early hoping to have the place to myself for a bit for some photos, but there’s no one there to take photos of because I arrived two and a half hours early hoping to have the place to myself for a bit. I shoot what I can, what will look good before the crush of people arrives, but I’m sat at the bar waiting before long. Two hours before my first curtain, and I already smell terrible.

All around me is a flurry of activity from volunteers and festival organizers, activity I remember being part of from prior years, but have no place in now. The box of Cheddar Goblin that lives on the top shelf with the beer display mocks me. Is everyone else mocking me too? I hope they all realize I’m not here so early because I’m a loser, I’m here so early because I’m insane. Faust Cabernet, I’m going to have to remember that.

Fuzzy Head writer/director/producer/star/editor Wendy McColm made the film in five different stretches of production during the pandemic and was still tinkering with the version I saw, so I’m seeing the finalized version of the film for the first time – but it’s also the first time I’m seeing it on a screen that isn’t my computer. It’s in the upstairs theater, which was converted from the original balcony and started showing movies just a couple years ago now, and even in the context of this theater, it’s a unique space. The screen is almost swarming the audience, maybe 10 yards or so away from the front row, and the projector is angled such that just about anyone who stands up during the showtime will cast a shadow over at least the bottom part of the frame. Combined with designating this as their screen for 35mm prints, it makes watching a movie in the space a much more physical experience. There are reminders everywhere that what you’re seeing isn’t just someone’s imagination, it had to be made into a reality to be shot, and the mere act of showing it to you is a very physical thing as well.

I already adored Fuzzy Head, this tremendously personal voyage into McColm’s psyche, but there’s a tremendous amount of vibrancy and detail to it that I hadn’t appreciated on my desktop, and it would feel like seeing the film for the first time even if it weren’t a finalized cut.

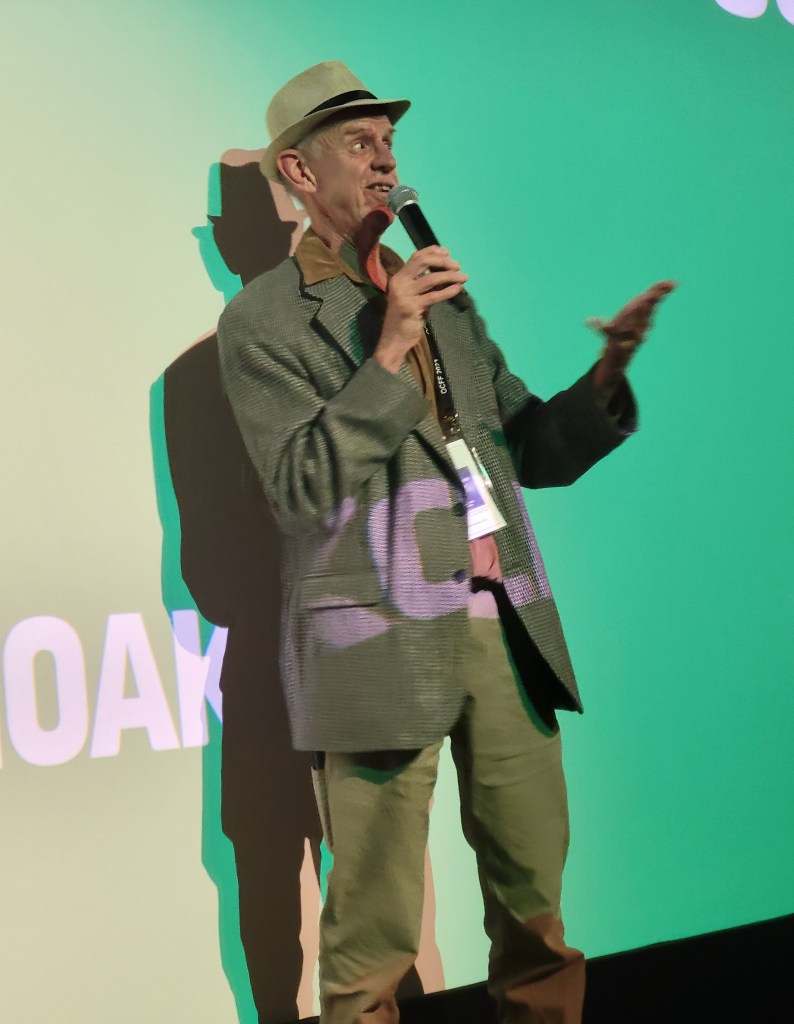

I wasn’t familiar with the work of Alex Cox, a furiously anti-capitalist Western filmmaker whose brief string of successes in the mid-‘80s slammed to a halt with Walker, which I would feel comfortable describing as his masterpiece despite knowing nothing else about him – Cox shares this belief. I’m going to have to spend some time getting up to speed on him.

The film is a satirical biopic of William Walker, a renaissance man who, with control of a mercenary group, attempted to colonize Nicaragua in the 1850s, ostensibly to establish an early version of the idea for the Panama Canal, a biography that Cox describes as extremely accurate but I don’t have time to verify for myself at the moment. The film ends with then-recent footage of Ronald Reagan insisting the U.S. would never invade Nicaragua just before the Iran-Contra affair broke in November 1986.

It’s the kind of anti-war satire that would go right over the heads of pro-war Americans – specifically the kind of person who insists that they’re anti-war, but talks frequently about an ever-expanding list of scenarios in which war is sadly necessary that is always suspiciously in line with current propaganda. Think Starship Troopers for an example that’s probably higher-profile today – another film made by an on-the-rise European auteur, Paul Verhoeven, that brought his Hollywood career to a screeching halt.

Walker is so on-the-nose that it’s almost traumatizing in 2023. What I key in on is a lot of Walker’s dialogue seems to be coming straight out of Dick Cheney’s mouth – he literally says “we will be greeted as liberators” at one point, and I start to wonder if Cheney is unironically quoting the film to help sell the Iraq War. Language about “spreading democracy” is thick throughout the film, and apparently it’s meant genuinely, with Walker at one point asking why Costa Rica and Panama don’t need democracy as well.

This is probably going to need to be a point of ongoing research for me – I was born in 1992, five years after Walker came out, and was 9 years old on 9/11. I think I’m pretty well-versed in post-9/11 cinema, but that’s from a perspective that’s still completely blind to more overtly anti-war cinema, especially of the ‘80s when the cinema was a place to process the guilt and nihilism of the Vietnam War.

The last film of the evening is The Lost World, an early adventure film that follows an expedition deep into the Amazon Rainforest where one scientist has reported dinosaurs still roam. To my 21st Century eyes it looks like an early version of King Kong, which would hit screens eight years later, but it reveals a great deal about interwar attitudes. The motivation of the male lead in the shoehorned love story, journalist Edward Malone, is desperate to join the expedition because his fiancée tells him she’d never marry a man who hasn’t been to war.

The idea of dinosaurs still roaming the Earth is a much more overtly political assertion in 1925 than it would be today – paleontology and the theories of evolution are still very recent things, and most of the people who would be watching this movie were raised on the idea that the Genesis narrative is the literal creation of the world, that Adam personally named all the plants and animals that exist today. Extinction as a concept, the idea that creatures might have existed on this planet that are no longer, and its implications, humans could be one day be one of them, are all incredibly divisive ideas, especially in the roaring ‘20s when everyone thought the wars were all over and we could keep burning coal forever – again, the idea that the planet is capable of changing to the degree that we have seen it change since then is seen as nonsense by many at this time. It’s obviously still seen as nonsense by many today, and between Walker and The Lost World, a lot of present-day imperialism and climate denial makes a ton of sense. The concepts feel both more mundane as we explore the words, actions and thought processes of the people who think these ways, but also bigger and more threatening as we see how far back they stretch without really changing.